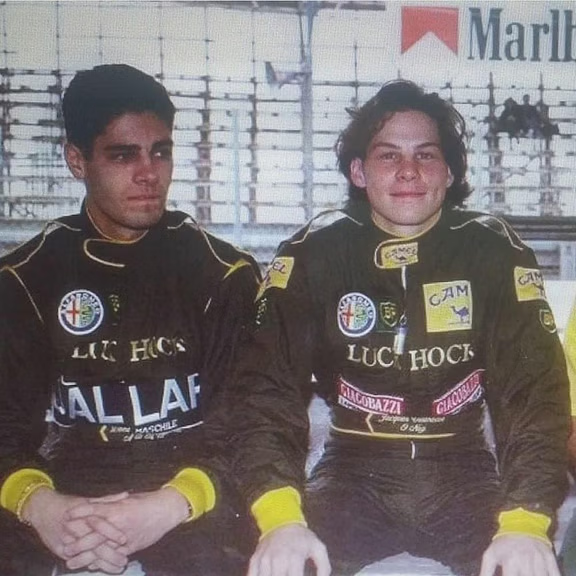

The Italian former Simtek driver (94-95) in Formula 1, with experience in LeMans, CART and many other championships, spoke to Marios Gantzoudis about his career, his difficult experience in F1, the time he had coffee with Michael Schumacher, and what it’s like to meet Enzo Ferrari in person!

The name Domenico “Mimmo” Schiatarella means little to most people. A quick glance at his CV may not impress many. However, he is a driver with over 35 years of experience in motor sports, having even reached Formula 1! From a child who set out to pursue his dream, to now, as a middle-aged man who trains professional drivers, he remains a man passionate about motor sports and, as you will realize from our conversation, a passionate Italian!

Let’s start at the very beginning. Before Formula cars, before international circuits — who was young Mimmo, and what drew you to racing?

It’s a long story. I was born in Milan, but when I finished high school at 14, I discovered that there was a school in Maranello founded by Enzo Ferrari himself (Dino Ferrari School) where they taught how Ferrari engines were made. I immediately fell in love with it, so I left everything behind to study there. It was difficult to leave my family and friends behind, but I was determined to become a racing driver.

My family was normal (not rich), so studying in the field of motor sports was the best way to stay close to my passion. My father promised to help me if I did well in school, and in the end, he bought me a go-kart. I didn’t race much in karts, though—I went straight to Formula 4. My father even sold α house to buy my first Formula 4 car.

I won immediately in Formula 4, then the Formula 2000 championship, and later in Formula 3 (2nd in 1991). Before racing, I was just a passionate student with the courage to leave home and pursue my dream.

There is a famous saying that goes: There are two religions in Italy: the Catholic Church and Ferrari. I imagine you would agree with that.

Yes, definitely. I love Ferrari. At that time, I mean, for me, Ferrari was, let me say, a real Ferrari, when Enzo Ferrari was still alive. Now times have changed, now there is a lot of “politics.” The mentality has changed.

You mentioned Enzo Ferrari, and if I’m not mistaken, you had the opportunity and honor of meeting him as a child.

Yes, of course! I studied at his school and had my first interview with him in his office, and then I met him a few more times. In fact, after my father, he was definitely my first source of inspiration. He asked me, “What do you want to do?” and I replied, “I want to be your driver,” and he said, “Wow, you’re crazy, but it will be a long road for you, but keep going and stay focused.” I will certainly never forget those words. He was a truly charismatic man. He really intimidated people because his strong character made it difficult to even talk to him. But he gave me a lot of strength, and so I always remember that it’s worth the effort.

It must have been amazing. You mentioned your success in the lower categories in Italy, your titles in F4 and F2000, and you spent many years in Italian F3 with great results. That was a time, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when this series was extremely competitive. Apart from the titles and victories, what did you learn from those early years?

I learned to fight. The competition was fierce back then, with 50 cars and some incredible drivers! At that time, Italian F3 was the best in the world. Competing against drivers like you know Mika Hakkinen, Jacques Villeneuve, Alex Zanardi, Michael Schumacher (in other F3 events) and maybe beating them, back then It meant nothing more than competing/ beating a friend. At the time, it was normal for me; I didn’t imagine that they would become Formula 1 champions and legends. But now I remember those days and I’m really happy!

Were there any defining moments during that period in F3 that made you believe that, ‘yes, I can make it to the top’? Because, as you mentioned, you were competing against future legends of motorsport. You competed against Michael Schumacher and Mika Häkkinen. You were teammates and rivals with Jacques Villeneuve and Alex Zanardi.

Yes, Alex is one of my best friends, but unfortunately he is very ill and I pray every day that he will recover soon, but it will be very difficult, like Michael Schumacher. Yes, Jacques and I were on the same team, and I remember that as someone who had more experience and something of an expert, I helped him because he was younger, and I gave him a lot of information about setting up the car. I had a great time with Jacques too.

And yes, at the time I felt extremely confident because i would compete hard against these drivers and beating them. But I didn’t expect that all of them would become Formula 1 champions. You see, here in Italy we have a problem with the federation. In the Italian federation, everything is centered around and connected to Ferrari. And believe me, we had so many good drivers in Italy, talented drivers with the potential to become champions like Zanardi in IndyCar, but they never had the opportunity to race for a top F1 team.

Look for example at drivers like Vincenzo Sospiri or Andrea Montermini. They performed brilliantly in F3000 against future greats like Damon Hill and Rubens Barichello as teammates respectively. But then Damon went on to become world champion and Vincenzo disappeared. Rubens became a top driver for Ferrari and Andrea disappeared. Unfortunately, the Italians didn’t have the opportunities they deserved.

But do you see this changing with Kimi Antonelli, perhaps because he drives for Mercedes and not Ferrari?

Fortunately, after many, many years, we now have an Italian driver in a top team. I am so happy that Toto Wolff believes in him and I believe that one day he will become one of the fastest drivers in F1. And I thank Mercedes for giving him this opportunity and believing in him. But unfortunately, Mercedes is not Ferrari, and I think Kimi should race for Ferrari at some point because he is Italian. It would be a very nice story.

Let’s go back to those Formula 3 years. Aside from success and wins, you even got the Autosprint gold medal. But even though you were seen as a really good driver, you struggled with your next step. Why?

Lack of money (sponsors). I did a test in Formula 3000 with Mansell Madgwick (Nigel Mansell’s team) at the Valelunga circuit. I tested the car and set the fastest time. Alan McNish, Vincenzo Sospiri, David Coulthard and many other drivers were there. But then, unfortunately, they asked me for a million lira (budget) for the season and I didn’t have any sponsors. So I realized that my career in Europe was over and I decided to go to North America to try racing in Formula Atlantic.

Even then, money and sponsors were hugely important in the development of a career. Do you think the situation is better today, now that we have many team academies? Back then, there was only the Marlboro academy.

No, definitely. Definitely. You’re right. Now, if you’re very good from an early age, these academies will support you. I mean, it’s hard to judge, because some academies require a budget to get into an academy like Ferrari or Alpine. You need money, especially in the beginning. But certainly, if you are a truly talented individual, such as Kimi Antonielli, it is easier to reach Formula 1 nowadays. In my time, there were no academies, no support. It was just your performance and, in a way, having or finding sponsors. That’s all. It was a little more difficult. Also, testing was limited and the races were more dangerous in a way. It’s different, completely different nowadays.

So you went to Canada and, as you mentioned, you sought to participate in Formula Atlantic, but things took a while to get going, didn’t they?

I decided to move to Canada to join a Formula Atlantic team because I had a contact there. The team owner was an Italian-Canadian and he said, “Okay, you can come here, but there’s no opportunity for you at the moment.” So I worked for about seven months as a mechanic, since that’s what I had studied. Then, luckily for me, Patrick Carpentier, who was the official driver, fell off his bike and broke his leg. And that was my chance, because they put me in the car right away.

We went for a test drive and I was much faster than the others. So they said, okay, okay. So we’ll take you. And so I became Rookie of the Year in Formula Atlantic after only 4-5 races. Then there was a German who had a team in CART, Formula Indy, and we made a deal for the following year. Everything happened so fast. I was just working as a mechanic, without a car, but then I saw the opportunity and I grabbed it. And from there, I returned to real motorsport.

There was some success in North America in 1993 and then in 1994, with some races in CART, and then came the opportunity for what you had been dreaming of all along. The opportunity to race in Formula 1 with Simtek. How did this opportunity arise?

Basically, in a race at Mid-Ohio, I set the second-fastest time in wet conditions. Then Gerhard Berger’s manager saw me and said, “I need to talk to you.” Because it had been two weeks since Roland Ratzenberger’s death. Initially (at Simtek) they tried Andrea Montermini, but he had a terrible accident in Barcelona and broke his legs. Then they tried Jean-Marc Gounon, but he didn’t perform well enough.

*Editor’s note:Domenico may be referring to someone connected to Gerhard Berger, as it is well known that the Austrian did not have a manager. Perhaps it was someone from his circle..*

And then this guy was here at Mid-Ohio and he said, “Listen, we’re looking for drivers and you impressed me. I’m a manager for Gerhard Berger. I know how a driver should perform. And I was so impressed with you. I’d like to give you a chance.” I laughed because to me it was like a joke. I had just arrived in America and this guy was offering me Formula 1. I said okay and gave him my card.

After two weeks, he called me and said, “Listen, you need to come here immediately to take the Superlicense test. “What???” I said. And he said, “Yes, there’s an opportunity. We want to test you and we want to go to Estoril to do the license test,” etc., etc. It was a very difficult decision for me. I had just joined IndyCar and was doing very well, even though I had an older chassis with this German team.

I also spoke on the phone with the president of the championship, and he told me not to go. He said they needed me here in America because I am Italian and because I was doing well. He told me, “You have a huge career ahead of you. Why would you go to Formula 1 with this team (Simtek) where one driver died and the other is in the hospital? Why would you want to go there?” I mean, it was so complicated. The car turned out to be so bad. I can say that now, but back then I was young. I didn’t have a manager behind me. I was on my own. And I had always dreamed of F1 my whole life. So when they gave me the opportunity, it was very difficult to say, “No, I’m not coming.”

But now, when I think back to that day, I definitely should have stayed in IndyCar, and my career could have been completely different. Later, Zanardi came here too. I had a test scheduled with Chip Ganassi’s team, but I gave it up to go to Estoril. And then Alessandro kind of took the spot that I might have had if I had stayed. It was a very good opportunity, but I preferred F1.

So you entered F1 during the 1994 season, which was a tragic and chaotic season, with changes to the rules and then more changes to the rules after the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger. How did you feel when you were offered the position and when you agreed to go for tests and then race for Simtek? Considering that… That was the year your idol, Senna, died, and the day before, your predecessor, in a way, also died. What were you thinking?

To be honest, I wasn’t thinking. I was just seizing the opportunity. Of course, I felt sorry for Roland and for Senna, who was my idol, but I didn’t think about the consequences of my choice, that I might die like Roland or be seriously injured like Andrea. I felt that I could do better and that I could give the team a good result. A race driver can’t think, “This is a dangerous car” or “That friend died.” Of course, you have to be smart, but when Formula 1 calls, how can you say, “I’m not going”? It’s difficult.

During that era, testing was practically unlimited. At least for the top teams that had the money and personnel. How often did you go testing with Simtek? How were the tests conducted?

I didn’t even do a single kilometer as a test. Especially with the ’95 car, we arrived at the first race in Brazil with zero tests during the winter. And then, due to some problem, with the fire extinguishers if I remember correctly, we didn’t even run in the first free practice sessions. Then my steering wheel broke in qualifying and I crashed.

So things were still complicated for me. And then in Argentina, because we had done only a few laps and needed data, they sent me out in incredibly bad conditions, with a lot of rain, to do laps because we needed data all the time. For me, of course, it was good publicity, because I was the only idiot out on the track in Argentina with so much water on the track. And they told me to push the car to get data but not to crash, because if, for example, a wing broke, we would have to go home as there were no spare parts.

And then I remember that it was really cool because Michael Schumacher came to my hospitality area and asked me where the most critical spots were, where there was a risk of aquaplaning. You know, it was nice for me because he came to me to ask for some information about the track conditions because I was the only crazy person out there in those conditions. Then we sat down and had a coffee and talked a little about the setup of the single-seaters, blah, blah, blah. And yes, it was nice for me!

You mentioned Argentina. That race is usually considered a missed opportunity for Simtek because the car looked promising. Both you and Jos Verstappen were doing quite well before you retired.

Indeed, we were doing very well. I was on track to finish sixth until I suffered a puncture. So I had to make an extra pit stop compared to the others and finished 9th. But back then, only the top six got points. If I had finished 6th, it might have changed the trajectory of Simtek because more sponsors would probably have come on board.

There are reports from small teams at that time that attention was usually focused on the No. 1 driver or the one who brought in the most money. Was that the case at Simtek?

When I arrived in F1, I did a good job, apparently, though not an exceptional one, because 1994 was a very complicated year. But in 1995, the car was a little better, more competitive. But the problem I had was that I had Jos Verstappen as my teammate and I couldn’t see his telemetry, for example. Two years after the team went bankrupt, my mechanic revealed to me that I had a completely different car from Verstappen. You know, because he was a Benetton test driver, he had a contract with Flavio Briatore, and the team was getting gearboxes from Benetton.

I had a completely different car, in terms of engine, gearbox, suspension, differential. Everything. And it drove me crazy because I was usually 1.5-1.8 seconds slower than Jos in qualifying, and I really wanted to understand why, where I was going wrong, or where I could improve. But for me, as I said, it wasn’t even possible to check his telemetry data, and it took two years before I found out the truth.

But then in Monte Carlo, it was very satisfying for me because Monte Carlo was the last race for Simtek and they finally had two equal cars. They put the standard gearbox, the standard differential, everything standard. And then I was 0.9 seconds faster than him in Qualifying. So for me it was huge.

*Domenico may have been confused, as in the final results of Monaco qualifying he was 20th and Verstappen 14th. However, he was faster than Verstappen for almost the entire weekend.

But then, for the race, they put very old gearboxes in both of our cars, which were sure to “blow up” after 300 meters. And after the accident that happened at the first turn of the race and the red flag came out, I shifted down a gear and then I couldn’t shift up, and neither could Jos. And do you know why they did that?

Because they wanted to save money on rebuilding the two engines after the race. They saved £300,000 because they were sure it was the team’s last race, but we didn’t know that. That was a really awful move by that English team, by those really bad people. And now, after 30 years, I can say that.

These people weren’t like Minardi, who put money in and wanted a real racing team. They just wanted money, and honestly, looking back now, all the people behind the project, even if I had got that point and we had maybe raised a lot of money, they would probably have just pocketed it and probably after Monaco, the story would have ended in the same way.

You mentioned Monaco. There is a notorious clip from a spin you had at La Rascasse. Was there a specific reason why you found it difficult to get back on track? Because there is a case that is not identical, but similar, with Ricardo Rosset in 1998, and he was labeled as stupid or incompetent. What happened in your case? Was there some kind of damage?

It was a clutch issue. As I mentioned, I had a different clutch, a more standard transmission assembly. I also had difficulty starting from the pit lane because the clutch travel was less than a centimeter; it engaged almost immediately. And first gear was very “long,” so to speak. And so, because I couldn’t just turn off the engine and stop because I had to do laps on the track, I was frantically trying to turn it in the right direction.

But with that “travel,” it was almost impossible, and yes, I ended up looking incompetent and foolish. Maybe it would have been better to turn off the engine, get a red flag, and then they would have taken me back to the garage. But I really tried hard, but it wasn’t possible.

So, after just seven races, your Formula 1 career was over. How would you describe it? Although it was short, would you say you had more to give? Were you satisfied with the mere fact that you competed in F1, fulfilling a dream of yours?

Of course, I’m not happy. I could have done much more because in the lower categories I was able to compete on equal terms with the best. Those who later became super-fast drivers. I still hold the lap record at Monte Carlo for F3, for example. What I did at Simtek was obviously not enough to stay in Formula 1, but maybe if I had had the same equipment as Jos(Verstappen), I might have done better.

But in any case, we have to remember that it was Simtek, not Williams, Ferrari, or Benetton. So we always started from around 15th to 24th place. I could maybe start from 15th place. But I’m happy that at least I survived, while others didn’t make it or were seriously injured. But of course it could have been better with different equipment, a different car, and so on and so forth.

So, after Formula 1, you competed in various types of categories in the late 1990s and early 2000s with great success. What is your favorite moment from those years?

I have fond memories of the prototype races. I remember Le Mans when we finished 6th overall (1999). We had a private team with the official Nissan engine. And yet we managed to beat the official Nissan team. What else? I remember when I took pole position at Silverstone against some very good cars. Audi, BMW, Panoz… I was really flying at Silverstone. But then, unfortunately, while I was in first place, my throttle cable broke.

A two-euro part broke and it was crazy. Otherwise, we could have won. But I showed that I was fast. I also have very good memories of the ALMS (American LeMans Series) and GT. We performed very well with my teammates (e.g., victory in the 1996 6 Hours of Vallegunga, victory at Road America in 1999, Asian GT championship in 2008), and yes, I can be satisfied. But I never had the opportunity to race for the factory team.

You mentioned Le Mans, where you competed twice. What was it like to drive in the most famous endurance race?

I believe that all drivers should compete in Le Mans during their career, because that is, I think, the real essence of motorsport. You need to have a really good strategy. You have to stay focused for so many hours. You are very tired. You have to push to the limit, it’s really very complicated, maybe at one point the track is wet and elsewhere dry, at night it’s difficult and there’s a lot of traffic. It’s a very good memory.

In addition to competing in races yourself, in 1993 you also started teaching and coaching drivers. How did this passion for teaching begin?

Let me say that I know quite a few drivers who are extremely talented and fast, but they can’t coach someone and guide them properly. I don’t want to name names, but I was the director of a driving school at Ferrari for several years and I saw quite a lot. You have to have the passion and be able to convey it to whoever you are coaching. How you communicate with people is very important, and you have to find the point of understanding. You have to give the right input at the right time, especially when you’re sitting next to them and they’re driving at the limit.

It’s quite complicated. And for me, it’s wonderful to coach. I discovered that I really enjoy doing this kind of work. Now, you know, I manage five Emil Frey Racing drivers in the Ferrari Challenge, and in every race, I coach them all. I give them the right picture of what they need to do, etc., etc. So I’m happy. I like it.

So, today your official role in racing is training Ferrari Challenge drivers.

Yes, of course, apart from that, I also have my own small driving school for individuals who want to go to the track. We have a couple of Ferraris that we can use for people who are first studying, then we create online racing driving lessons, and they start at two hours. Then they do a Zoom call with me. We go into the technical side of things and then we go to the track and do, you know, a day at the track where they can actually apply what they’ve learned in theory to the track. You know, with me sitting next to them, yeah, it’s nice. I enjoy doing that.

So that is the ultimate goal of DS Performance Driving: to transform ordinary drivers into higher-level drivers and maximize their potential.

That’s right. Yes.

You were a youngster at the Dino Ferrari school. You have represented Ferrari in races. You have taught for Ferrari. How proud is Domenico Schiattarella of himself?

I am proud because I achieved it without any support from anyone, except my father, of course. I was able to reach F1, which for many drivers is a dream. But I don’t know how I found a way to get there. Honestly speaking, that’s why I’m proud in a way. But of course, when you’re there and you know your potential, then you want more. You want to achieve more. And I never really had the chance, I was always racing with an old chassis or an old engine. I never had the right equipment to really compete with my rivals. But still, I’m proud. I can’t change the past, and everything is fine.

So, to end our conversation on a more entertaining note, I would like to ask you a few quick questions. What was your favorite car that you ever drove in any racing series, in any year?

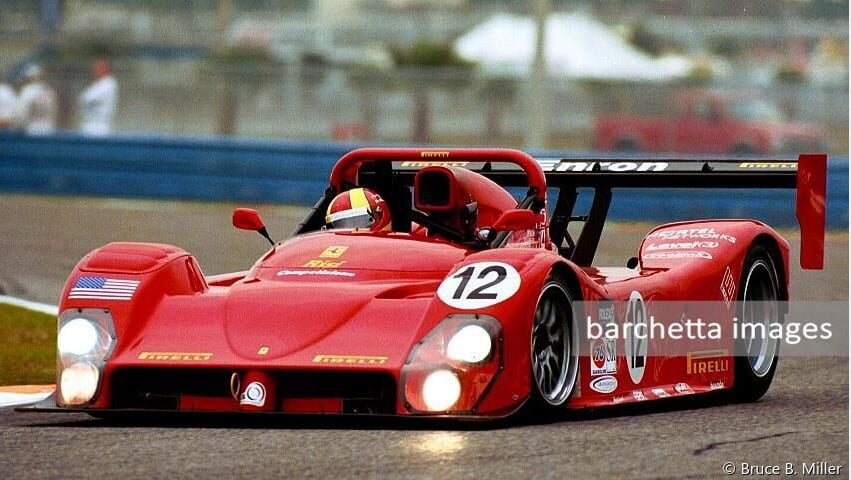

The car that is still close to my heart was the Ferrari 333 SP, in which (Alex) Caffi, (Alan) McNish, and I started from the front row at the 24 Hours of Daytona and didn’t win the race because we blew the engine. It was a car with an incredible sound, as it had a Ferrari V12 engine from Formula 1. I felt really good with that car. And unfortunately, we lost the IMSA championship because fuel consumption was a little high. But yes, the Ferrari 333 SP. And in a three-hour race, we had to do a kind of “splash and go” in the last five minutes, because otherwise we would have run out of fuel.

And even though I was constantly in first place, I ended up in second, third, or fifth place. At that time, Giuliano Michelotto was in charge of the engines. He wasn’t able to save five minutes of fuel in three hours. We were already at the limit, and he said, “Sorry, Mimmo, I can’t do any more than that. You have to slow down.” I said, okay, but if I slow down, they’ll overtake me. But again, to answer your question, yes, the Ferrari 330 SP was one of the best cars for me.

Who was your favorite teammate?

My favorite teammate was Emanuele Naspetti. We spent three or four years in America together. We are still very good friends. We are like brothers and keep in touch.

Who was your favorite opponent?

Well, definitely, if we go back to F1, 100% Michael Schumacher. He definitely raced with Benetton, with Ferrari, with super teams. But again, as I said before, the episode when he came to Argentina was a real honor for me, we were friends and for me it was kind of wow. He came to ask me, what do you think? That’s why I say Schumacher, because I think that for me, after Senna, he was one of the top drivers in the world.

Now to something more recent. Do you think that Ferrari, with its current combination of Hamilton, Leclerc, and Vasseur, will win again in Formula 1?

No. For me, you definitely need a leader, and you definitely need good drivers. And I think Charles is a good driver. Lewis was a very good driver, even if he’s not my favorite. But in Formula 1, you also have to develop the car properly. McLaren has done this with steady progress, while Ferrari is not improving properly. Perhaps it’s because of the complexity and politics within the team, something you don’t see at McLaren. In contrast, in the Hypercar program, two people—Antonello Coletta and Amato Ferrari—made the right decisions, without interference, and succeeded. This shows that success comes when there is clear leadership and a clear goal.

Who do you think will win the championship this year? Lando Norris or Oscar Piastri?

In my opinion, Oscar Piastri. Although I’m not a huge fan of his, he has impressed me. He is really calm and cool, especially when there is a difficult situation, unlike Lando, who is a little more enthusiastic and cares more about his lifestyle around F1. I may be wrong, but I would bet on Oscar.

Okay, so for the last part, I’m going to say a few names and I want you to describe them in one word. We’ve talked about them in one way or another. I want you to describe Alex Zanardi in one word.

Superhero!

Mika Häkkinen

Cold

Jacques Villeneuve

Eccentric

Michael Schumacher

Dedicated

Ayrton Senna

God!

And finally, the most important of all, Domenico Schiattarella

A fighter!

Thank you very much for the chat, and I hope you enjoyed it!

I enjoyed it very much, thank you!